“As soon as my hands left the railing, it was instant regret”, says Kevin Hines, a suicide survivor. Statistically, only one percent of people who jump off the Golden Gate Bridge survive, which equates to about 40 survivors out of the estimated 2,000 who have jumped. Kevin’s poignant story of childhood trauma, mental illness, and recovery is chronicled in his aptly titled book, “Cracked, Not Broken”, which seems like an appropriate metaphorical title to describe both the reality and resilience of individuals who experience suicidal crises.

What regret did Hines connect with in that instantaneous moment when he let go of the railing? As we learn more about his story, we come to understand that his mental state that day on the bay bridge was one of hopelessness, sorrow, and desperation. Desperation, as he says, that someone would see his pain and offer to help. When no one did, a flood of suicidal core beliefs prompted him to act on his suicidal urges.

How do we, as clinicians, “see” our client’s suicidal pain? How do we “offer to help”? Part of that answer may lie in accepting a reality that can often be forgotten in the world of suicide prevention: most suicidal people do not want to die. While some reading this may already be acquainted with this fact, others may be utterly confused. What do you mean that people who are suicidal don’t want to die? Isn’t that what suicide is really about – death? Suicide can be about death. Suicide can also be about wanting the pain to stop, and not knowing how to make that pain stop other than to take one’s own life. Consider the analogy that 13-year-old Maddie Yates expressed in her journal writings shortly before she died by suicide.

“It's like someone's on the 12th floor, and the room behind them is on fire. And they're standing on the window ledge, and they have a choice whether to jump and get away from the fire or just stay and die a slow, excruciating death. It feels like that.”

Maddie’s words have become a leading analogy for understanding the distress that individuals may feel as they contemplate what they perceive as only two options: staying alive and burning (suffering) slowly or ending one’s life by (escaping) quickly to avoid the pain of the current life they are living.

Suicide may be less about death than we think. In Aaron Beck’s Suicide Mode conceptualization, we come to understand the interplay between thoughts and beliefs, emotions, physiology, and behavior as fundamental processes to fueling the suicide mode. In the suicide mode, people feel trapped. They can feel suffocated by the state of their psyche and it seems like there is no way out. Day in and day out they deal with mental agony and anguish that both frightens them and pushes them at the same time. Individuals often feel like death is the only way out, but at the same time, the human in them desperately wants to fight, to cling on to hope. To cling on to life. How do we help our clients cling on to life when they are seeing death as the only option?

Suicide advocacy groups such as the Zero Suicide Project have embarked on understanding the motivations for suicidality that extend beyond death. Their research and findings echo what Samaritans Project, a national suicide prevention and resource organization says, “The majority of people who feel suicidal do not actually want to die; they just want the situation they’re in or the way they’re feeling to stop. The distinction may seem small, but it is very important. It's why talking through other options at the right time is so vital.”

How often do we as clinicians directly ask our suicidal clients if they truly want to die or if they just want the suffering and pain to end? Their answers may surprise you. As helpers we should embrace the perspective that a suicidal client sitting in front of us may not seek or want death. Instead, they may want hope, reasons for living, and a trusted professional such as yourself to guide them in looking for the third alternative in suicide. Making assumptions that suicide equates to wishes for death is premature and not considerate of the complex nature of suicidality.

What is the third alternative? It is the option of finding ways to be in pain and stay alive, what Marsha Linehan, founder of Dialectical Behavior Therapy, refers to as the dialectical stance. They want to live so desperately, but they can’t seem to find a way to. They feel like they have exhausted all their options and the pain they are experiencing is well beyond them.

Linehan gives a nod to Beck’s Cognitive Theory model when she says, ““The desire to commit suicide, however, has at its base a belief that life cannot or will not improve. Although that may be the case in some instances, it is not true in all instances. Death, however, rules out hope in all instances. We do not have any data indicating that people who are dead lead better lives.”

Those familiar with Linehan’s DBT model may easily spot the irreverence in her last sentence, which aims to remind clinicians of our influence and responsibility to talk with clients about death, life, suffering, and the limitations of death because of the finality of suicide. What if the third alternative allows for clients to have more space to consider that their life is worth fighting for? Maybe there are ways to address the pain and suffering while staying alive and with the goal of finding reasons for living, and ultimately, hope.

How can clinicians invite this third alternative into the room with suicidal clients? Our initial efforts should be focused on thorough and comprehensive assessment and conceptualization. Each client’s suicidality is akin to their fingerprints; unique to them. Comprehensive models such as Aaron Beck’s (hopelessness), David Jobes’ (Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicide, CAMS), Tom Joiner’s (scales related to burdensomeness, thwarted belonging, and the acquired capability of suicide action), David Rudd’s (Suicide Cognition Scale), and Marsha Linehan’s (Reasons for Living and Dying) provide clinicians with effective tools to reveal your client’s unique suicide mode.

The power of Linehan’s validation-change model provides clinicians with another valuable skill to employ with suicidal clients. The validation component focuses on accepting and acknowledging an individual's thoughts, feelings, and behaviors without judgment. The change component focuses on identifying and changing negative or self-destructive behaviors. Conveying acceptance may sound like, “I hear that you are really suffering right now”, while an expression of change may be, “I believe that we can discover an alternative to you suffering this much so that you don’t want to kill yourself anymore.” Linehan strongly believes that introducing the validation-change model early with suicidal clients is essential to begin exploring the third alternative.

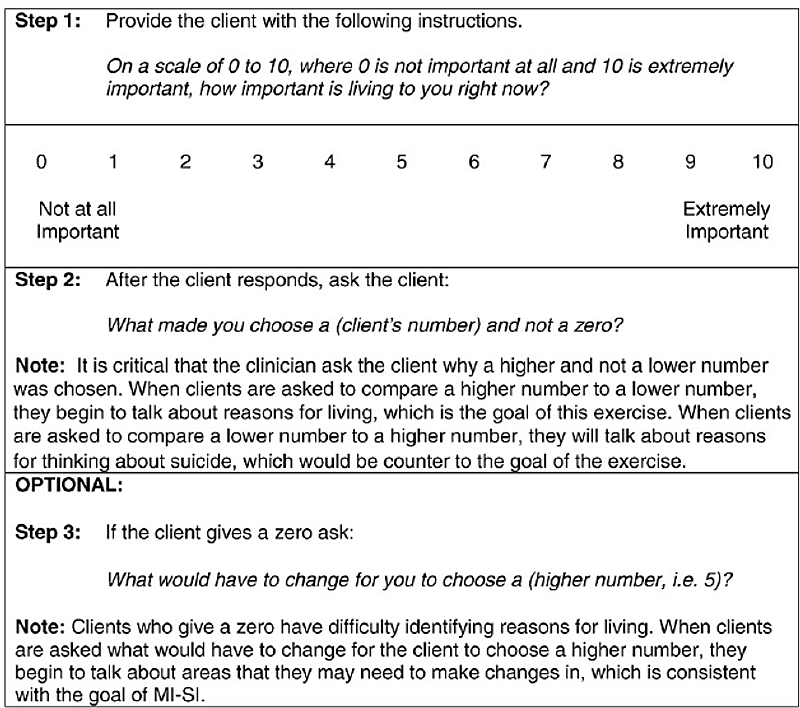

Motivational Interviewing provides a useful tool to evoke reasons for living in suicide as opposed to focusing on the death desires that exist in suicide. As you can see from the three steps in the chart below, the use of scaling can be an effective way to elicit motivations for living and promote intrinsic hope. This approach can enhance a client’s ability to mitigate or cope with suffering and thrive rather than just survive.

By having conversations with our suicidal clients about life rather than death, we can shift the paradigm and acknowledge with these individuals that we understand suicidality to be about more than just death. Suicide management can and should be about hope, resilience, and assisting clients in embracing the third alternative.

References and Resources:

Kevin Hines Story: https://kevinhinesstory.com/

Samaritan’s: https://samaritanshope.org/

Zero Suicide Project: https://zerosuicide.edc.org/

Motivational Interviewing Importance of Living Ruler article: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Importance-of-Living-Ruler_fig1_247331745

Meichenbaum, Donald. 35 Years of Working with Suicidal Patients: Lessons Learned: https://melissainstitute.org/documents/35_Years_Suicidal_Patients.pdf

Suicide Mode (Aaron Beck and David Rudd): https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-suicidal-mind/202401/what-is-the-suicidal-mode

Validation: Walking the Middle Path: https://www.ou.org/assets/Validation-.pdf